Lovelock Cave is a big crack in the West Humboldt Mountains overlooking the Humboldt Sink, now a balding patch of scrub, a remnant of the Lahontan Sea of 10,000 years ago. From Lovelock, take Amherst Avenue (just south of the McDonald’s) west from Main street. It’s pavement at first, then well-maintained dirt road suitable for the proverbial ‘family sedan’.

It had been a habitation for human beings for thousands of years. This was a well-known landmark to the wagon train pioneers of the 1850s and ’60s: this is where the Humboldt River, a slow, shallow, brackish trickle by this point, disappeared altogether into the broad expanse of mud. The cave was central to the lives of the humans who lived in willow huts and derived their sustenance from the broad lake and lush marshlands stretching out below.

It had been a habitation for human beings for thousands of years. This was a well-known landmark to the wagon train pioneers of the 1850s and ’60s: this is where the Humboldt River, a slow, shallow, brackish trickle by this point, disappeared altogether into the broad expanse of mud. The cave was central to the lives of the humans who lived in willow huts and derived their sustenance from the broad lake and lush marshlands stretching out below.

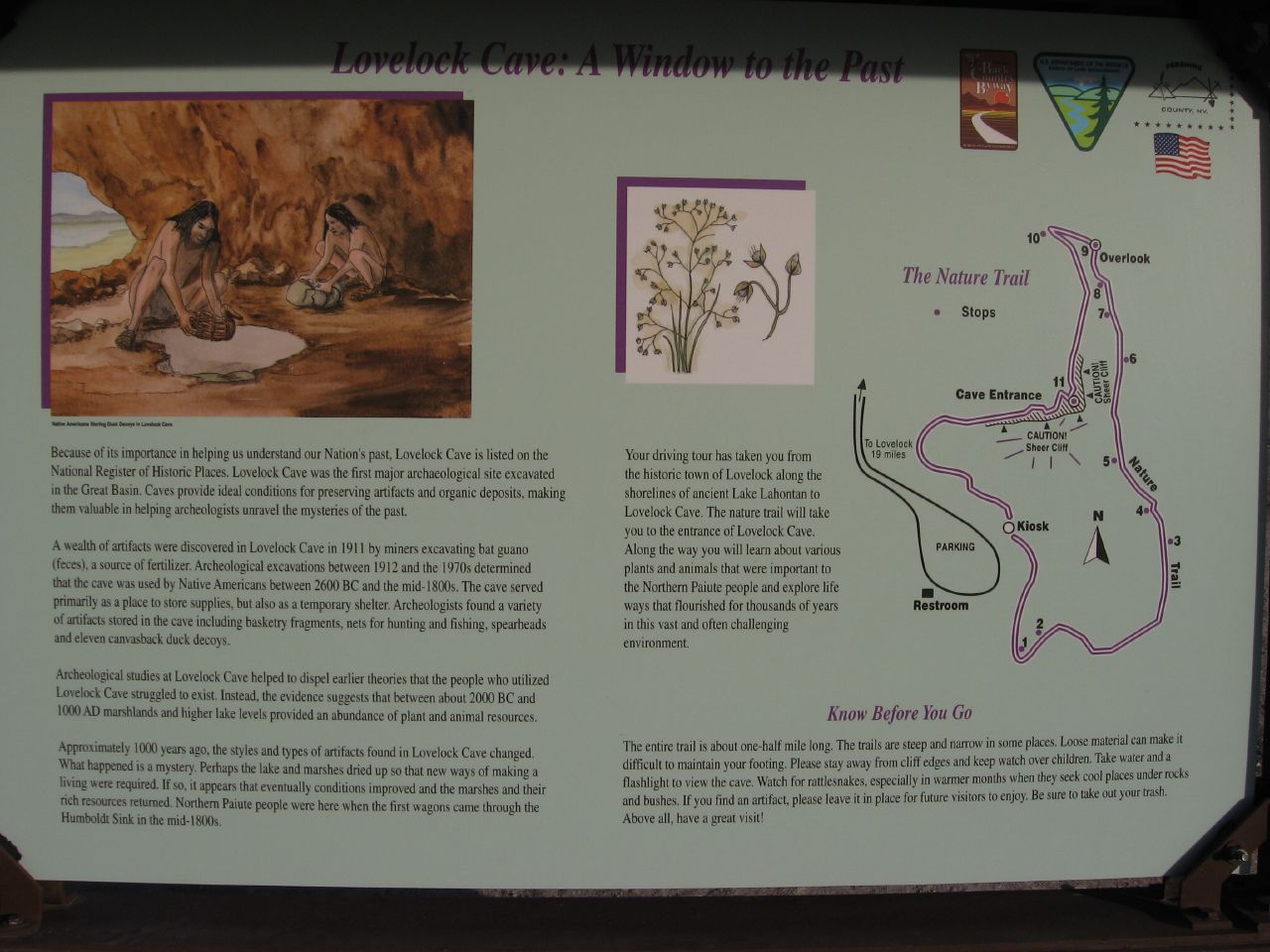

The BLM has made a parking lot, equipped it with toilets and information kiosks, and built a Nature Trail to the cave, which was the communal vault for the People. If one of the Cat-tail Eaters were to be away for some weeks, he would bring his duck decoys and fishing tackle to bury them out of harm’s way in the cave. Not because he was concerned about theft; the People didn’t steal from each other. It was damage from rodents or weather that worried them if they were to leave their valuables in a hut down by the lake.

The BLM has made a parking lot, equipped it with toilets and information kiosks, and built a Nature Trail to the cave, which was the communal vault for the People. If one of the Cat-tail Eaters were to be away for some weeks, he would bring his duck decoys and fishing tackle to bury them out of harm’s way in the cave. Not because he was concerned about theft; the People didn’t steal from each other. It was damage from rodents or weather that worried them if they were to leave their valuables in a hut down by the lake.

The cave is about 150 feet long and 35 feet wide, and one of the most important classic sites of the Great Basin region. It was formed by the lake’s currents and wave action; people occupied it for more than 4,000 years, first as a rock shelter, in use as early as 2580 BC but not intensely inhabited until around 1000 BC.

The cave is about 150 feet long and 35 feet wide, and one of the most important classic sites of the Great Basin region. It was formed by the lake’s currents and wave action; people occupied it for more than 4,000 years, first as a rock shelter, in use as early as 2580 BC but not intensely inhabited until around 1000 BC.

In 1911 two miners, David Pugh and James Hart, removed about 250 tons of bat guano from the cave. An archeological review of the excavation states “[the guano] was dug up from the upper cave deposits, screened on the hillside outside the cave, and shipped to a fertilizer company in San Francisco.”

In 1911 two miners, David Pugh and James Hart, removed about 250 tons of bat guano from the cave. An archeological review of the excavation states “[the guano] was dug up from the upper cave deposits, screened on the hillside outside the cave, and shipped to a fertilizer company in San Francisco.”

The dry environment of the cave resulted in a wealth of well-preserved artifacts that provide a glimpse on how people lived in the area. The miners were aware of the artifacts but only the most interesting specimens were saved, and the loss of material and damage to the site strata was considerable. L.L. Loud of the Paleontology Department at the University of California was contacted by the mining company when the refuse left by the ancient people proved so plentiful that fertilizer could no longer be collected.

The dry environment of the cave resulted in a wealth of well-preserved artifacts that provide a glimpse on how people lived in the area. The miners were aware of the artifacts but only the most interesting specimens were saved, and the loss of material and damage to the site strata was considerable. L.L. Loud of the Paleontology Department at the University of California was contacted by the mining company when the refuse left by the ancient people proved so plentiful that fertilizer could no longer be collected.